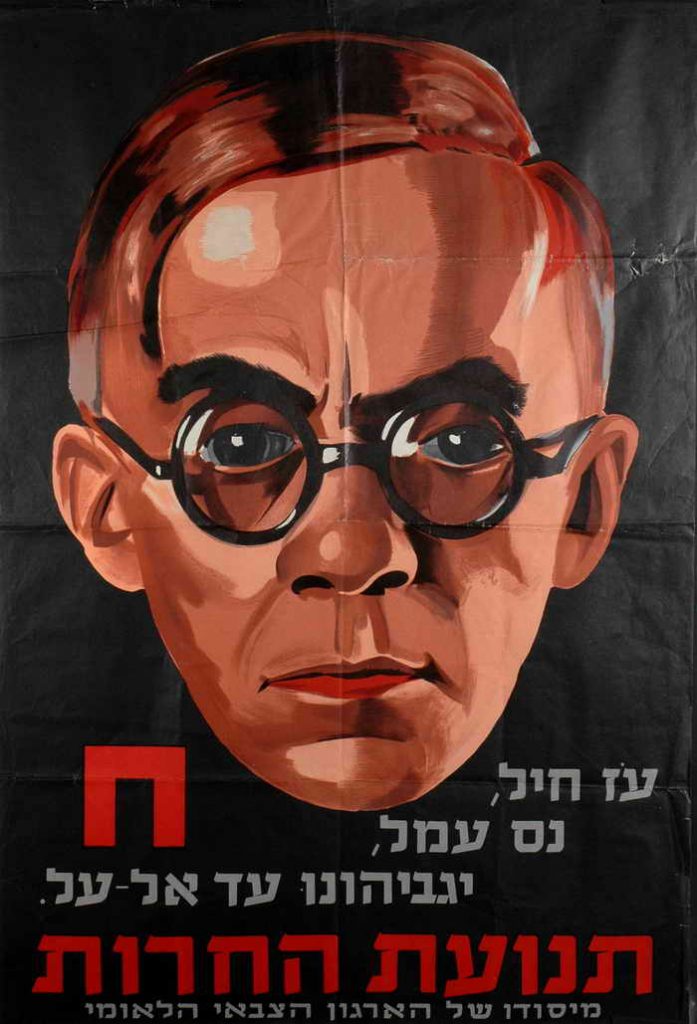

Ze’ev (Vladimir) Jabotinsky was born in Odessa in 1880 to a liberal Russian Jewish family. He worked as a journalist in Rome and Vienna and at an early age began to devote his energies and skills as a writer, orator, and polemicist to the Zionist cause. During the Great War he persuaded the British to form Jewish volunteer units within the British army and served as an officer in its Zion Mule Corps in Egypt. During the Great War, he had shared a flat in London with Chaim Weizmann, the leader of the Zionist movement. Jabotinsky had gone down to the East End seeking to form a Jewish Legion for service with the British in Palestine. However, both the British and the Jewish residents of Whitechapel were not so keen on the idea, and he had been pelted with rotten fruit. Jabotinsky settled, therefore, for the small Zion Mule Corps in Egypt that the British offered him.

In 1923 Jabotinsky published The Iron Wall, an article in which he described the course the Zionist movement should follow in order to realise its goal of the creation of an independent Jewish state in Palestine. At this point the British governed the territory upon which the Zionists wished to build their state, after acquiring it from the Ottomans after the Great War. During the War Britain had claimed the future ownership of the territory through the issuing of the Balfour Declaration of 1917.

The Zionist movement, having supported Britain’s Balfour Declaration, had the challenge of creating a Jewish majority in the territory, where there was a large native population of non-Jews, after the War, and ultimately acquiring the land of Palestine from the British in order to fully control their destiny.

In The Iron Wall Jabotinsky criticised the Zionist establishment for ignoring the Arab majority in Palestine and their interests. He asserted that the Zionist establishment held a fanciful belief that the technological progress and economic capabilities that Jewish colonists would supposedly bring to Palestine would endear them to the local Arab population. Jabotinsky thought that belief was fundamentally wrong.

There was a belief—or a pretence at belief—that the Jewish State could be constructed in Palestine without harm being inflicted on the native population. The reasoning was that the native population was so backward that they would not notice the framework of this state being constructed around them, or their will to existence was so weak that they would just wither away as it took shape in their midst. It was sometimes asserted that it actually would be a boon to the native population, because they had lived for generations under the ramshackle and decrepit Ottoman Empire. Their land was now to be infused with progress – Jewish progress – and a vigorous, hard-working people who would bring development and prosperity to all, including the native population itself.

Jabotinsky was keen to dispel such myths and illusions. He said that the Palestinian Arabs were a people of substance who needed to be conquered and subjugated in order that the Jewish State could be successfully imposed on Palestine, and it might flourish. He insisted that the Jews were, in actuality, colonisers and all self-respecting indigenous peoples had fiercely resisted colonisers in self-defence. To Jabotinsky, the Arabs of Palestine, like any native population throughout history, would never accept another people coming to dominance in their own homeland and who wished to take from them their land. Jabotinsky believed that Zionism, as a Jewish national movement, would have to physically conquer the Arabs for control of their land and territory: “Every native population in the world resists colonists as long as it has the slightest hope of being able to rid itself of the danger of being colonised.”

There was no reason why the Zionist Jews should expect any different with the Palestinian Arabs. And if the Jews were serious about their Zionism they needed to be realistic about what this required them to do to the Palestinians to make their dream a reality.

Jabotinsky was of the belief that the Zionist movement should not waste its resources on endearing itself to the natives through bringing economic and social progress to them. Zionism’s main focus should be on developing Jewish military force, a metaphorical Iron Wall, so powerful that it would compel the Arabs to accept a Jewish state on their native land – progress or not: “Zionist colonisation … can proceed and develop only under the protection of a power that is independent of the native population – behind an iron wall, which the native population cannot breach.”

The chief architect of the alliance between the Zionist movement and Great Britain was Chaim Weizmann. Weizmann had managed to forge a wartime alliance with Britain, after long fruitless years of effort, by offering the services of the Jews for the winning of the Great War. At that point in the War, which Britain was struggling hopelessly to win, it was making promises to all and sundry, many of them in contradiction, to anyone it thought could tip the balance against the Germans and Ottomans. It perceived the Jews to be an asset to the enemy and saw a worldwide Jewish conspiracy ranged against Britain. So, Britain took up Weizmann’s offer to use the Zionist movement to overcome the Jewish conspiracy.

The only aim of Britain at that point was to win the War, no matter the cost, and it was thought that the future could look after itself. Without victory in the Great War, it had taken on, the British Empire could not survive, with the loss of prestige it would suffer.

Weizmann’s attitude toward the Palestine Arabs was shaped by his broader strategy of gaining British support for Zionism. The deeper and more complex his negotiations with the British government became in the course of the Great War, the less attention he paid to the local difficulty for Zionists of the Palestine Arabs. To elicit British support for what he termed a Jewish commonwealth in Palestine, he had to minimise the danger of organised Arab resistance. In making his case to Britain, he appealed not only to the British Imperial interest in having an asset in a region of great strategic importance, but also to British idealism. Weizmann’s efforts achieved success on 2 November 1917, with the Balfour Declaration.

In 1921 Jabotinsky was elected to the international Zionist Executive. From the very start he was at odds with Weizmann, and in 1923 he resigned from the Zionist Executive, arguing that its policies, especially its acceptance of the 1922 British White Paper, would result in Zionist failure in Palestine. The 1922 White Paper attributed tensions in Palestine to “exaggerated interpretations” of the Balfour Declaration, clarifying its intent to mean that while the “Jewish national home” is to be established in Palestine, that did not mean Palestine was to become wholly Jewish or Jewish-dominated.

At successive Zionist congresses Jabotinsky established himself as the chief spokesman for the opposition. However, there was no fundamental difference between Jabotinsky and Weizmann regarding the role of Britain in Zionist affairs. Both men were disciples of Theodor Herzl and assumed that the support and protection of a Great Power were absolutely indispensable to Zionism until it could gather strength and stand on its own two feet against the inhabitants of Palestine.

Jabotinsky had a strong pro-Western orientation rejecting the view that the Jews were an Oriental people. He believed in the cultural superiority of Western civilization: “We Jews have nothing in common with what is denoted `the East and we thank God for that,” he declared. The East, in his view, represented backwardness and passivity, social and cultural stagnation, and despotism. Although the Jews originated in the East, they belonged to the West culturally, morally, and spiritually. Zionism was conceived by Jabotinsky not in terms of a return of the Jews to their homeland, but as a colonial implant of Western civilization in the East. This worldview translated into a geostrategic conception in which Zionism was to be allied with European Imperialism against the Arabs in the eastern Mediterranean.

The root cause of Jabotinsky’s dispute with the official Zionist leadership, however, was his conception of the Jewish state. He laid down two principles that formed the core of the Revisionist Zionist ideology and its political program. The first was the territorial integrity of Eretz Israel, the Land of Israel, from the River Jordan to the Mediterranean Sea, within the British Palestine Mandate. The second was the immediate declaration of the Jewish right to political sovereignty over the whole of this area conquered by the British.

The Zionist objective raised the question, what should be the Zionist attitude toward the native inhabitants and what should be their status within a future Jewish state? Jabotinsky’s answer was contained in his two articles he published in 1923 under the heading “The Iron Wall.” They gave the essence of Zionist Revisionist theory on the Arab question and provided its battle cry. The first article is entitled “On the Iron War (We and the Arabs).”

Moderate Zionists criticised the Iron Wall article because it offended their moral susceptibilities – and their relationship with the British. The British had described the Balfour Declaration in idealist terms as a progressive, benevolent and beneficial enterprise for the Jews, Arabs, the region and the World. Weizmann did not wish to dispel such notions lest it spoil what he had painstakingly built. Even if Zionists knew in their heart of hearts what they were actually doing it was better for them all, and for their relations with their British patron, that they believed they were doing good in the world. This is Liberal Zionism.

Jabotinsky replied to the moderates with a second article, entitled “The Morality of the Iron Wall,” in which he turned the tables on his critics. From the point of view of morality, he argued, there were really only two possibilities: either Zionism was a positive force in the world, or it was a negative one. This question had already been answered because it had required an answer before one became a Zionist. Since all Zionists had concluded that Zionism was, indeed, a positive force, “if the cause is just, justice must triumph, without regard to the assent or dissent of anyone else.”

An argument against Zionism was that it violated the democratic right of the Arab majority to their own national self-determination in Palestine. After all, they were the large majority there, not the Jews, who were to be imported. Jabotinsky responded that the Jews had a moral right to return to Palestine and that the enlightened world of the West had acknowledged this right through the Balfour Declaration. He then turned to the argument that the method of the Iron Wall was immoral because it tried to settle Jews in Palestine without the consent of its inhabitants. He pointed out that since no native population anywhere in the world would willingly accept an alien majority, the only logical conclusion for anyone who accepted any rights for the Palestinian Arabs would be for them to renounce altogether the idea of a Jewish state, and Zionism.

Jabotinsky asserted that Zionism was the most moral of objectives:

“A sacred truth, whose realization requires the use of force, does not cease thereby to be a sacred truth. This is the basis of our stand toward Arab resistance; and we shall talk of a settlement only when they are ready to discuss it.”

Although the Iron Wall became the program of Revisionist Zionism, its real message was often misunderstood, even by Jabotinsky’s own followers. For Jabotinsky, the Iron Wall was not an end in itself, but a means to the end – of breaking Arab resistance to the Zionist project and establishing its onward expansion. Jabotinsky argued that once Arab resistance had been broken, a process of change would occur inside the Palestinians, with the moderates coming to the fore, over the resistance. Then and only then would it be time to start serious negotiations with them, from this position of strength. In any negotiations the Jewish side should offer the Palestinians some degree of civil and national rights. Jabotinsky did not spell out in this article what precisely he meant by “national rights,” but other pronouncements suggest that what he had in mind was some degree of political autonomy for the Palestinians within a Jewish State – perhaps the kind of rights now enjoyed in Gaza and the West Bank.

Jabotinsky’s Iron Wall was directed against those who were suggesting that the Jewish State could be constructed seamlessly in Palestine in a kind of progressive evolutionary and transformative way, without damage to the native population. In the Iron Wall he called those people the “vegetarians” who would lead Zionism to vegetate, to become passive and decay in a lack of vigour.

Albert Montefiore Hyamson (‘A.M.H.’), a Jewish British civil servant, was a good example of an important “vegetarian”. Hyamson had penned an article for The New Statesman on 21st November 1914, entitled The Future of Palestine, which apparently had a great effect on Lloyd George, before he became the Prime Minister and approved the Balfour Declaration. It was written just when Britain had declared war on the Ottoman territories, signaling the absorption of its territories, including Palestine.

Here is some of that article:

“More than once in the past Turkey has received notice to quit Europe, but this is the first time that the liquidation of Turkey in Asia has become a definite prospect, and with Mr. Asquith’s words at the Guildhall the hopes of the Zionists have suddenly passed from an ideal into a matter of practical politics…

With the advent of Young Turkey… all possibility of such an event disappeared; and with it passed away Zionism as a political movement… Zionism has now became entirely a movement for the recreation, after the lapse of two thousand years, of a Jewish centre in Palestine. Jerusalem was to be, not the capital of a Jewish State, but the center of Jewish culture… Left alone the future of the Jews in Palestine would have been secure… But the country is now in the melting-pot and the crisis has come too soon for the Jews to be able to cope with it unaided. The crisis, however, is not one for the Jews of Palestine alone, but for the Jews of many other lands…

Today we are told is the day of small nationalities. Their interests are to be considered when peace is concluded. It should not be overlooked that the Jews of Palestine… are also a small nationality… the weakest of the nationalities and they cannot stand alone. For many years, perhaps for centuries, they will need a protecting Power while they grow into a nation. To give Palestine self-government today would be a blunder and a crime…

Christendom owes a debt to Jewry for the persecutions of the past nineteen hundred years. It would seem that she now has the opportunity of commencing to pay it. Let Britain remember her past and think of her future, and secure to the Jews under her protection the possibility of building up a new Palestine on the ruins of her ancient home.”

This was very effective bait. It was certainly crafted with great care and contained all the essential elements of what the Jews could do for the British Empire, when required. But it would be mistaken to believe that the raised hopes of British Zionists produced the British interest in Palestine. It was the British designs on Palestine that made the Zionist project a possibility – and then a reality.

Hyamson played on the reality of the situation England was creating in the Middle East by exclaiming that: “Left alone the future of the Jews in Palestine would have been secure… But the country is now in the melting-pot and the crisis has come too soon for the Jews to be able to cope with it unaided.”

By throwing the region into the “melting-pot” England was disrupting the comfortable and profitable position the Jewish communities enjoyed within the Ottoman Empire. And they were removing them from a stable order to place them amongst Arabs who were also being fed modern notions of nationalism. In such circumstances Britain owed a responsibility to the Jews of protection, particularly given the history of “the persecutions of the past nineteen hundred years.”

Hyamson did not bother himself with the difficulties this seemed to present in balancing up the interests. That was not politic for Zionists. For one thing he thought that if the decadent and decrepit Ottomans could do effective balancing for centuries surely the British Empire could, and better. How wrong he was!

Hyamson was the Director of the Department of Information which the British Foreign Office set up in 1917 to spread propaganda amongst Jewish communities about the Balfour Declaration. Part of his work was in organising aeroplanes to drop leaflets over Germany and Austria as part of the Department of Information‘s work.

Back in 1898, during his visit to Palestine, the Kaiser had spoken favourably of the Zionists and advocated increased autonomy for the Jewish settlements. But the Ottoman administration rejected any formal autonomy, restricted land transfers, and preserved the arrangements which proved conducive to good relations between Arab and Jew for centuries. Hyamson obviously believed that England could preserve good relations in the region, as the Turks had done, and build a substantial Jewish colony at the same time. But subsequent events proved how mistaken he was in this view.

It is very difficult to read the following passage, with the knowledge of what transpired, without getting the impression that the author was hoping, rather than knowing, that this would be the case. This is Hyamson, writing for The New Europe at the time of the Balfour Declaration. The New Europe was a periodical in which influential people helped Britain map out the future Europe it was going to organize once it had won its Great War:

“A common fallacy is the belief that the aim of Zionism is the creation of an independent Jewish State, into which a vast body, perhaps the majority, of the Jews of the Diaspora, will migrate. To those who hold that view Zionism is an Imperialist movement, one aimed at the conquest, perhaps peaceably, if not, forcibly, of the Holy Land, carrying with it, presumably, the ousting of its non-Jewish populations. But this is very far from the truth. To responsible Zionists the attainment of the status of an independent State in Palestine is not a matter of practical politics at the present day. The Jewish people is not ripe, nor can it be in the near future ripe, for independence. In the political sphere all that Zionism asks immediately is autonomy for the Jewish population, present and future, of Palestine, self-government in domestic, in internal matters, an extension of the autonomy which the Jewish colonies already enjoy under the Turkish regime, independence in matters of education, of local government, of religion – gas and water Home Rule one might say, but rather more than that: cultural Home Rule.

As the Jewish population increases the area covered by this system of Jewish autonomy will increase. It will not increase at the expense of the non-Jewish population, nor will its liberty, its right to self-government, diminish the liberty or the rights of its neighbours. There is room in Palestine for at least another million Jews without displacing the inhabitants. Palestine is an empty land, a deserted land, not a desert, one that has been deprived of its people. For its regeneration a population must be provided, and it is only from the Jewries of the Dispersion that the population will come.

That it is quite practicable for self-government of this character to be enjoyed by the Jewish population, is shown by the experiments of the past thirty years. During that period between forty and fifty self-governing Jewish settlements, ranging in size from three or four thousand inhabitants to less than a hundred, have sprung up. The Turkish Government has granted an autonomy that is practically complete. The only grounds of interference by the Central Government are in respect of taxation… and serious crime…

The relationship between these Jewish colonies and their Arab neighbours is in every respect friendly. The benefit to the latter is direct and is admitted…

Zionists do not desire to obtain absolute control of Palestine… They want also the protection of a Power that will secure the land against all possibility of outside aggression. Politically, the fondest dream of the Zionists is the incorporation of Palestine in an Empire whose basis is liberty and justice…” (The New Europe, 27 September 1917)

So why did this Ottoman Garden of Eden for Arab and Jew so quickly become a Hell on Earth for the native population under British auspices?

It would have been a realistic calculation to assume that there would be no real conflict of interest between Arab and Jew, provided that Britain honoured its agreement with the Shereef of Mecca and Britain recognised an Arab State at the end of the War. Faisal, who was to be the King of that state had agreed to accept the Balfour Declaration on condition that Britain honoured its commitment to accept the Arab State. However, Britain divided the Arab State with France, and then divided its own share of the spoils into a series of puppet-states. And that put the position of the Jews and Arabs in the new State of Palestine on an entirely different footing than Hyamson may have imagined.

According to the Encyclopaedia Judaica Albert Hyamson became anti-Zionist after serving as Britain’s Chief Immigration Officer in Palestine between 1921-1934. That shows that he was a sincere “vegetarian” and not cut out for the real work of Zionist conquest. Perhaps he had been assimilated too much and become an English gentleman.

Britain, in attempting to turn the Jews, made a fatal miscalculation in its ecstatic state of Biblical fervour. If Britain believed the Jews to be mere mercenaries of Germany, why could they not also be the same of Britain? It was never considered that in turning the Jews into nationalists of Zion that might not cause them to cease being mercenaries. Would they then not see themselves, after their return to Zion, as real nationalists with national independence as their aim – the only objective worthy of the name of any self-respecting nationalism? And would that not repel them from the Imperial motherland – which was not really a mother to them at all but really just a surrogate?

Finally, what would the attitude of thoroughgoing nationalists, imbued with notions of religious and racial superiority, make of a large and hostile group within their midst? That is the question Jabotinsky asked in his Iron Wall and he also had an answer for it.

Ze’ev Jabotinsky had an interesting relationship with Ukrainian nationalism, and indeed its most antisemitic variety. Jabotinsky was a native of Odessa, a Russian city with a large Jewish population. He was convinced, however, that Ukrainians were a distinct nation, and he formed a deliberate alliance with Ukrainian nationalists. Jabotinsky reasoned that if the Tsars were able to subdue Ukrainian nationalism, other potential nations, such as that promoted by the Zionist movement, would just be assimilated by the Russian State. In 1911, an exchange between Jabotinsky and the prominent Russian intellectual Peter Struve, published in the magazine Russian Life, put the nationalities question on the agenda in Russia. Lenin’s own personal notebooks show that the Struve-Jabotinsky debate was among his first readings on the nationalities question. The debate began when Jabotinsky authored a series of essays in 1909 demanding that Russian intellectuals stop trying to dismiss Ukrainian nationalism as bogus. Jabotinsky, writing in 1911, reasoned that the future of the Zionist project depended on the success of the Ukrainian nationalist development.

Jabotinsky wrote:

“The question of whether Russian Jewry is fated to assimilate or to develop as a separate nationality depends mainly on the answer to the following momentous question: in which direction is Russia developing—toward a nation-state or toward a “state of nationalities”? In a unilingual state, an ethnic minority, particularly a dispersed one, will inevitably assimilate sooner or later, but its fate would be completely different in a country where several nationalities and languages were allowed to develop freely.” (Israel Kleiner, Here and Elsewhere, From Nationalism to Universalism: Vladimir (Ze’ev) Jabotinsky and the Ukrainian Question.)

Whether Jews could escape catastrophic assimilation entirely depended on the fate and success of Ukrainian nationalism. For Jabotinsky, Ukrainian nationalism was the only organised force in the Tsarist Empire large enough to resist suppression and could thereby force an adjustment in its policy toward minorities in general.

Symon Petliura, President of the short-lived Ukraine republic, is one of the founding fathers of Ukrainian nationalism. He has had a street named after him quite recently in Kyiv. In the Jewish narrative, Petliura is identified with pogroms in which tens of thousands of Jews were slaughtered by Ukrainian nationalists. W.E.D. Allen’s History of Ukraine has the following to say about 1919 in the Ukraine:

“What made the ‘Petlyurian’ campaign for ever memorable in Podolia was the extent and cruelty of their pogroms against the Jewish population. Pogroms began in January during the retreat of the ‘Petlyurians’ from the Kiev region when a particularly brutal slaughter took place at Belaya Tserkov, They continued in Podolia throughout the months of February, March and April, and what was probably the greatest pogrom of all time was enacted in the frontier town of Proskurov… All the combatants in the Ukraine Civil War of 1919 took part in Jewish pogroms… but the ‘Petlyurians’ undoubtedly distinguished themselves most in this direction. According to official Jewish sources (Ostjudische Archiven, Berlin) the ‘Petlyurians’ killed off 17,000 persons… The ‘Petlyurians’ also occupy first place for the number of organised pogroms – 493… How far Petlyuria himself was guilty in the organisation of these pogroms is difficult to say… But to persuade these Haydamaky (Ukrainian marauders) to any moderation was no easy task.” (pp.309-10)

So, while it was a given that most Ukrainian nationalists were pogromists it was not easy to say whether Petlyuria’s command was a restraining or inciting influence on his forces, who were undoubtedly worst among the Ukrainians at attacking and killing Jews. The Ukrainian commander at Proskurov, Ivan Semesenko, employed the common belief of “Judeo-Bolshevism” as justification, accusing Jews of disloyalty to the Ukraine Peoples Republic and sympathy for the Bolsheviks. Petliura said the same thing in telegrams and to Jewish leaders.

After independent Ukraine was defeated by the Red Army, Petliura found refuge in Poland, which was fighting against Soviet Russia. He offered Galicia (Western Ukraine) to it and planned to return to Ukraine at the head of an army of exiled ex-patriates to establish a Ukrainian nationalist state. Ze’ev Jabotinsky, by then a leading figure in the Zionist movement, signed an agreement with Petliura in 1921, that involved units of Jewish soldiers enlisting and going with Petliura’s army of liberation to oust Soviet rule.

Clearly Jabotinsky’s hatred of Russia was one reason behind the proposal. Publicly, he rationalised his offer to Petliura by claiming that the Jewish divisions in Petliura’s army would defend the Jewish population from possible future pogroms by Ukrainians, which he understandably expected within a Ukrainian state.

Jabotinsky’s suggestion allowed Petliura to claim that he was not antisemitic, and that the pogroms were simply “unfortunate” past events that had occurred in the heat of battle. Jabotinsky aided Petliura in rescuing his reputation by lifting the burden of the anti-Semite label from him. Jabotinsky said that all Petliura did wrong was failing to stop the Ukrainians from killing tens of thousands of Jews. He was not antisemitic himself. Jabotinsky even said defiantly to any Zionist who might doubt the wisdom of his actions: “When I die, you can write on my grave: ‘This was the person who signed an agreement with Petliura'”

In 1926, Petliura was assassinated in Paris by a Jew, Sholom Schwartzbard, who was seeking to avenge the murder of his family in a pogrom by Ukrainian nationalists. Schwartzbard was acquitted in court and for years served as a symbol of pride among Zionists. In 1967, on the initiative of Menachem Begin, his body was exhumed and transported to Israel for reburial in an official state ceremony. Ukrainian nationalists viewed Schwartzbard’s act as part of a Jewish-Bolshevist conspiracy.

Jabotinsky’s agreement with Petliura never materialized, but it caused serious controversy during the 12th Zionist Congress in Carlsbad. It created a deep schism between Jabotinsky, and the Zionist leadership headed by Chaim Weizmann, and was one of the reasons for the establishment of the Zionist Revisionist movement, which broke off from the World Zionist Organization. Ever since, the Zionist movement has done its best to sweep the affair under the carpet.

A very large proportion of the US foreign policy establishment is composed of Jews hostile to Russia and eager for Washington to make war on it. Some of Kyiv’s most vociferous supporters are in this camp, despite what Ukrainians did to the Jews in the past (and Soviet Russia did for them). One wonders if they have the Ukrainian people’s best interests at heart, or do they see them as disposable material, given the Ukrainian history with the Jews.

One thing is certain – they are at one with the position of Ze’ev Jabotinsky.

Finally, The Jewish Standard noted the following interesting fact in its edition of 15 February 2024:

“For the Israeli right-wing Likud party, which has been in power in the Jewish State for many years, it is Jabotinsky who is a political inspirator and ideological beacon. And the father of the current Israeli Prime Minister, Bentzion Netanyahu z’’l, was an assistant to Ze’ev Jabotinsky’s personal secretary in his youth.”

What is happening in Gaza and the West Bank today, directed by Benjamin Netanyahu and his government, is perhaps best described as Jabotinsky’s Iron Wall.

The Iron Wall (We and the Arabs) 1923 by Vladimir (Ze’ev) Jabotinsky

Contrary to the excellent rule of getting to the point immediately, I must begin this article with a personal introduction. The author of these lines is considered to be an enemy of the Arabs, a proponent of their expulsion, etc. This is not true. My emotional relationship to the Arabs is the same as it is to all other peoples – polite indifference. My political attitude is characterised by two principles. First: the expulsion of the Arabs from Palestine is absolutely impossible in any form. There will always be two nations in Palestine – which is good enough for me, provided the Jews become the majority. Secondly: I am proud to have been a member of that group which formulated the Helsingfors Program. We formulated it, not only for Jews, but for all peoples, and its basis is the equality of all nations. I am prepared to swear, for us and our descendants, that we will never destroy the principle of equality and we will never attempt to expel or oppress the Arabs. Our credo, as the reader can see, is completely peaceful. But it is absolutely another matter if it is ever possible to achieve a peaceful aim through peaceful means. The answer to this question does not depend upon our relationship with the Arabs, but entirely on the Arabs’ attitude to us, and to Zionism.

After this introduction we can proceed to the point. Voluntary agreement is not possible. That the Palestine Arabs of the Land of Israel should willingly come to an agreement with us is beyond all hopes and dreams at present, and in the foreseeable future. This inner conviction of mine I express so categorically not because of any wish to dismay the moderate faction in the Zionist camp but, on the contrary, because I wish to save them from such dismay. Apart from those who have been virtually “blind” since childhood, all the other moderate Zionists have long since understood that there is not even the slightest hope of ever obtaining the agreement of the Palestine Arabs of the Land of Israel to “Palestine” becoming a country with a Jewish majority.

Every reader has some idea of the history of other countries which have been colonised. I suggest that he recall all known instances. If he should attempt to seek but one instance of a country settled with the consent of the native population, he will not succeed. The inhabitants (no matter whether they are civilized or savages) have always put up a stubborn resistance to the colonists. Furthermore, how the settler acted, whether decently or not, had no effect whatsoever. The Spaniards who conquered Mexico and Peru, or our own ancestors in the days of Joshua ben Nun behaved, one might say, like plunderers. But those “great explorers,” the English, Scots and Dutch who were the first real pioneers of North America were people possessed of a very high ethical standard; people who not only wished to leave the redskins at peace but could also pity a fly; people who in all sincerity and innocence believed that in those virgin forests and vast plains ample space was available for both the white and red man. But the native resisted both barbarian and civilized settler with the same ferocity. Every native population, civilized or not, regards their lands as their home and wants to retain mastery of them, refusing to admit new masters, even as partners or collaborators.

And so, it is for the Arabs. Peace mongers in our midst attempt to convince us that the Arabs are some kind of fools who can be tricked by a concealed formulation of our aims, or who can be bribed to abandon their birth right to Palestine for cultural and economic advantages.

I flatly reject this assessment of the Palestinian Arabs. Culturally they are 500 years behind us. They have neither our endurance or our determination, but they are just as good psychologists as we are and their minds have been sharpened just like ours. We can talk as much as we want about our good intentions, watering down our aims with honeyed words to make them palatable; but they understand us as well as we understand ourselves and our aims and what is not good for them. They look upon Palestine with the same instinctive love and true fervour that any Aztec looked upon his Mexico or any Sioux looked upon his rolling prairies. To think that the Arabs will voluntarily consent to the realisation of Zionism in return for the moral and economic conveniences which the Jewish colonist brings with him is infantile. This childish fantasy of our “Arabophiles” comes from some kind of contempt for the Arab people, of some kind of unfounded view of this race as a corrupt mob to be bribed in order to sell out their homeland for a railroad system.

This view is absolutely groundless. Individual Arabs may perhaps be bought off but this hardly means that all the Arabs in Eretz Israel are willing to sell a patriotism that not even Papuans will trade. Every indigenous people will resist alien settlers as long as they see any hope of ridding themselves of the danger of foreign settlement.

That is what the Arabs in Palestine are doing, and what they will persist in doing as long as there remains a solitary spark of hope that they will be able to prevent the transformation of “Palestine” into the “Land of Israel”.

Some of us imagined that a misunderstanding had occurred, that because the Arabs did not understand our intentions, they opposed us, but, if we were to make clear to them how modest and limited our aspirations are, they would then stretch out their arms in friendship. This belief is utterly unfounded, and it has been proved so time and again. I need recall only one incident of many. Three years ago, during a visit here, Sokolow delivered a great speech about this very “misunderstanding,” employing trenchant language to prove how grossly mistaken the Arabs were in supposing that we intended to take away their property or expel them from the country, or to suppress them. This was definitely not so. Nor did we even want a Jewish state. All we wanted was a regime representative of the League of Nations. A reply to this speech was published in the Arab paper ‘Al Carmel’ in an article whose content I give here from memory, but I am sure it is a faithful account. Our Zionist masters are unnecessarily perturbed, its author wrote. There is no misunderstanding. What Sokolow claims on behalf of Zionism is true. But the Arabs already know this. Obviously, Zionists today cannot dream of expelling or suppressing the Arabs, or even of setting up a Jewish state and government. Clearly, in this period they are interested in only one thing – that the Arabs do not interfere with Jewish immigration. Further, the Zionists have pledged to control immigration in accordance with the country’s absorptive economic capacity. But the Arabs have no illusions, since no other conditions permit the possibility of immigration.

The editor of the paper is even willing to believe that the absorptive capacity of Eretz Israel is very great, and that it is possible to settle many Jews without displacing the Arabs. No misunderstanding exists. Zionists desire only one thing – and it is the one thing the Arabs do not want – Jewish immigrations and that Jews become a majority and Jewish government follows automatically. A Jewish state will be formed, and the fate of the Arab minority will depend on the goodwill of the Jews. But was it not the Jews themselves who told us how ‘pleasant’ being a minority was?

The logic employed by this editor is so simple and clear that it should be learned by heart and be an essential part of our notion of the Arab question. It is of no importance whether we quote Herzl or Herbert Samuel to justify our aims of colonization. Colonization carries its own explanation, the only possible explanation, and it is understood by every Arab and every Jew with his wits about him. Colonization can have only one goal. For the Palestinian Arabs this goal is inadmissible. This is in the nature of things. To change that nature is impossible.

A plan that seems to attract many Zionists goes like this: If it is impossible to get an endorsement of Zionism by Palestine’s Arabs, then it must be obtained from the Arabs of Syria, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and perhaps of Egypt. Even if this were possible, it would not change the basic situation. It would not change the attitude of the Arabs in the new Land of Israel towards us. Seventy years ago, the unification of Italy was achieved, with the retention by Austria of Trent and Trieste. However, the inhabitants of those towns not only refused to accept the situation, but they struggled against Austria with redoubled vigour. If it were possible (and I doubt this) to discuss Palestine with the Arabs of Baghdad and Mecca as if it were some kind of small, immaterial borderland, then Palestine would still remain for the Palestinians not a borderland, but their birthplace, the homeland and basis of their own existence. Therefore, it would be still necessary to carry on colonization against the will of the Palestinian Arabs, which is the same condition that exists now.

But an agreement with Arabs outside the Land of Israel is also a delusion. For nationalists in Baghdad, Mecca and Damascus to agree to such an expensive contribution (agreeing to forego preservation of the Arab character of a country located in the centre of their future “federation”) we would have to offer them something just as valuable. We can offer them only two things: either money or political assistance or both. But we can offer neither. Concerning money, it is ludicrous to think we could finance the development of Iraq or Saudi Arabia, when we do not have enough for the Land of Israel. Ten times more illusionary is political assistance for Arab political aspirations. Arab nationalism sets itself the same aims as those set by Italian nationalism before 1870 and Polish nationalism before 1918: unity and independence. These aspirations mean the eradication of every trace of British influence in Egypt and Iraq, the expulsion of the Italians from Libya, the removal of French domination from Syria, Tunis, Algiers and Morocco. For us to support such a movement would be suicide and treachery. If we disregard the fact that the Balfour Declaration was signed by Britain, we cannot forget that France and Italy also signed it. We cannot intrigue about removing Britain from the Suez Canal and the Persian Gulf and the elimination of French and Italian colonial rule over Arab territory. Such a double game cannot be considered on any account.

Thus, we conclude that we cannot promise anything to the Arabs of the Land of Israel or the Arab countries. Their voluntary agreement is out of the question. Hence those who hold that an agreement with the natives is an essential condition for Zionism can only reject and depart from Zionism. Zionist colonization, even the most restricted, must either be terminated or carried out in defiance of the will of the native population. This colonization can, therefore, continue and develop only under the protection of a force independent of the local population – an iron wall which the native population cannot break through. This is, in total, our actual policy towards the Arabs, whether we admit it or not. To formulate it any other way would only be sheer hypocrisy.

Not only must this be so, it is so whether we admit it or not. What does the Balfour Declaration and the Mandate mean for us? It is the fact that a disinterested power committed itself to create such security conditions that the local population would be controlled and deterred from interfering with our efforts at building a Jewish state.

All of us, without exception, are constantly demanding that this power strictly fulfil its obligations. In this sense, there are no meaningful differences between our “militarists” and our “vegetarians.” One prefers an iron wall of Jewish bayonets, the other proposes an iron wall of British bayonets, the third proposes an agreement with Baghdad, and appears to be satisfied with Baghdad’s bayonets – a strange and somewhat risky taste but we all applaud, day and night, the iron wall. We would destroy our cause if we proclaimed the necessity of an agreement and fill the minds of the Mandatory Power with the belief that we do not need an iron wall, but rather endless talks. Empty rhetoric of this kind is dangerous. Therefore, it is our pleasure and sacred duty to expose such talk and prove that it is both fantastic and dishonest.

Two brief remarks: In the first place, if anyone objects that this point of view is immoral, I answer: It is not true; either Zionism is moral and just or it is immoral and unjust. But that is a question that we should have settled before we became Zionists. Actually, we have settled that question, and in the affirmative.

We hold that Zionism is moral and just. And since it is moral and just, justice must be done, no matter whether Joseph or Simon or Ivan or Ahmed agree with it or not.

There is no other morality.

All this does not mean that any kind of agreement with the Palestine Arabs is impossible, only a voluntary agreement is impossible. As long as there is a spark of hope that they can get rid of us, they will refuse to give up hope, not for any kind of sweet words or tasty morsels, because they are not a rabble but a living people, perhaps somewhat tattered, but still living. A living people can only concede when there is no hope left for them. It is only when there is no longer hope in getting rid of us or making any breach in the iron wall, will their extremist leaders lose their sway, and influence transfer to moderate groups. Only then would these moderate groups come to us with proposals for mutual concessions. And only then will moderates offer suggestions for compromise on practical questions like a guarantee against Arab displacement, expulsion or equality and integrity.

I am optimistic that they will indeed be granted satisfactory assurances and that both peoples, like good neighbours, can then live in peace. But the only path to such an agreement is the iron wall, that is to say strong power in Palestine of a government that is not amenable to Arab influence or pressure. In other words, for us the only path to an agreement in the future is an absolute refusal to seek any agreement with them in the present.

Article published in Irish Foreign Affairs, Winter 2024.

Excellent artic

LikeLike