Did you know that President Trump is not a maverick and is simply returning the United States to the foreign policy of its founding fathers?

Thomas Jefferson, in his inaugural address of 1801, defined US foreign policy as “peace, commerce and honest friendship with all nations – entangling alliances with none.”

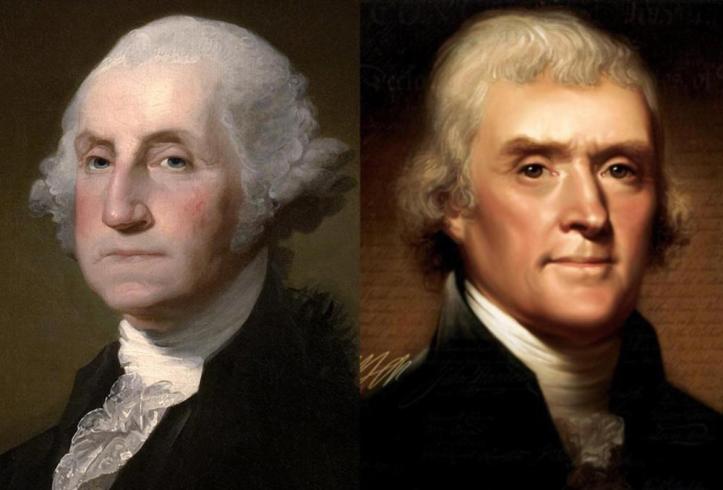

In his Farewell Address, George Washington had warned America against the perils of foreign entanglements and not to get involved in European wars. The fact that his predecessors have dangerously subverted Washington’s good advice is neither here nor there.

This is what Washington said in his farewell to the American people:

“Observe good faith and justice toward all nations. Cultivate peace and harmony with all…

In the execution of such a plan nothing is more essential than that permanent, inveterate antipathies against particular nations and passionate attachments for others should be excluded, and that in place of them just and amicable feelings toward all should be cultivated.

The nation which indulges toward another an habitual hatred or an habitual fondness is in some degree a slave. It is a slave to its animosity or to its affection, either of which is sufficient to lead it astray from its duty and its interest…

So, likewise, a passionate attachment of one nation for another produces a variety of evils. Sympathy for the favourite nation, facilitating the illusion of an imaginary common interest in cases where no real common interest exists, and infusing into one the enmities of the other, betrays the former into a participation in the quarrels and wars of the latter without adequate inducement or justification.

It leads also to concessions to the favourite nation of privileges denied to others, which is apt doubly to injure the nation making the concessions by unnecessarily parting with what ought to have been retained, and by exciting jealousy, ill will, and a disposition to retaliate in the parties from whom equal privileges are withheld; and it gives to ambitious, corrupted, or deluded citizens (who devote themselves to the favourite nation) facility to betray or sacrifice the interests of their own country without odium, sometimes even with popularity, gilding with the appearances of a virtuous sense of obligation, a commendable deference for public opinion, or a laudable zeal for public good the base or foolish compliances of ambition, corruption, or infatuation.

Against the insidious wiles of foreign influence (I conjure you to believe me, fellow citizens) the jealousy of a free people ought to be constantly awake, since history and experience prove that foreign influence is one of the most baneful foes of republican government.

But that jealousy, to be useful, must be impartial, else it becomes the instrument of the very influence to be avoided, instead of a defense against it. Excessive partiality for one foreign nation and excessive dislike of another cause those whom they actuate to see danger only on one side and serve to veil and even second the arts of influence on the other. Real patriots who may resist the intrigues of the favourite are liable to become suspected and odious, while its tools and dupes usurp the applause and confidence of the people to surrender their interests.

The great rule of conduct for us in regard to foreign nations is, in extending our commercial relations to have with them as little political connection as possible. So far as we have already formed engagements let them be fulfilled with perfect good faith. Here let us stop…

Harmony, liberal intercourse with all nations are recommended by policy, humanity, and interest. But even our commercial policy should hold an equal and impartial hand, neither seeking nor granting exclusive favours or preferences… constantly keeping in view that it is folly in one nation to look for disinterested favours from another; that it must pay with a portion of its independence for whatever it may accept under that character; that by such acceptance it may place itself in the condition of having given equivalents for nominal favours, and yet being reproached with ingratitude for not giving more.

There can be no greater error than to expect or calculate upon real favours from nation to nation. It is an illusion which experience must cure, which a just pride ought to discard.”

Washington was clear that to avoid being entangled in the constant wars of the European continent, waged by Europeans upon each other, there should be no entangling treaties or security guarantees given by the United States. And nations had to be treated fairly and equitably without distinction.

For the first 165 years of its history the United States did not form any alliance after the one it signed with France during the Revolutionary War.

President Trump is returning to George Washington and ending foreign entanglements. But he cannot return to Washington’s world, given the history in between and the US interests around the world. So, he has to play great power politics. If we are to believe that such good sense could never come from the mind of Donald Trump we can only surmise that these are the understandings of the deep state which chime with Trump’s practical mind and his instinct to oppose previous policies.

Andre Siegfried, the French writer noted around three-quarters of a century ago that the United States by its nature had two contradictory impulses. One was a desire for America First, and America only, and to further this policy there should be an avoidance of foreign entanglements.

The other was a universalism that encouraged some Americans to wish to spread the values of the great republic across the world.

Of its universalising impulse Siegfried said this of America:

“… this is shown in different ways. In the first place by Protestant moralizing, which is characteristically British, he looks at all problems from the moral angle and reserves for himself a privilege which gives him great satisfaction, that of passing judgment on others.

If other people do not comport themselves according to his ethical standards, he reproves them as if they had committed a sin. It is a legal type of moralizing which shows the American’s sincere attachment to certain principles handed down from the eighteenth century; they include an optimistic conception of human nature, faith in democracy, respect for international law, condemnation of conquest and particularly colonial conquests carried out overseas; if it is carried out on land, it is merely expansion…

It is not that the United States was not, before 1914, imperialist in her own manner, for indeed she was and did not attempt to hide it; but her expansion was limited to her own continent. When the Americans found themselves faced with world domination, they sincerely recoiled before the encumbrance of an empire; if destiny has finally imposed this responsibility upon them, it is against their wishes, unless, as the old saying goes, ‘L’appetit vient en mangeant’.” (America at Mid-Century, p. 337-40)

It was upon that second impulse that “the insidious wiles of foreign influence” particularly that of Britain, which felt itself as having some rights of ownership of America, worked to draw the US into foreign entanglements and wars.

This is the impulse which today Europe feels it is lost without.

In the decade or so before the Great War, Britain reached a stage in its history that was not dissimilar to what the US is facing today. It was the world hegemon and it wished to retain its global supremacy at any cost. However, having seen off the traditional rivals of France and Russia, it was realising that two other powers were rising that would mount threats to British world domination in the future – Germany and the United States.

Elie Halevy, the Anglophile French historian, was surprised that in all the articles produced in England during this period predicting war between Britain and others only one English writer entertained the thought that the next world conflict might be against the emerging United States of America.

This is a fact worth considering. After all, Britain had a habit of cutting emerging rivals down to size. The United States was the major obstacle to Britain’s world-wide domination and the biggest long-term threat. The US potentially represented a far stronger industrial and commercial competitor than Germany and had shown its ambitions in this area with the construction of the Panama Canal. On the other hand, Germany was the British Empire’s best customer in the world and the only state in the world that bought from England nearly as much as it sold to the British Empire.

But whilst Britain had developed a very aggressive attitude to its other Imperialist rivals, it shirked a conflict with America and neatly sidestepped any disputes which would have been made occasions for war with other nations.

Two serious territorial disputes arose between Britain and America. In 1895 Venezuela occupied a piece of British Guiana and when Britain threatened action, President Cleveland invoked the Monroe Doctrine to warn off the Royal Navy. Although Lord Salisbury rejected Cleveland’s right to do this he backed away from conflict and accepted the referral of the dispute to arbitration. In 1903, Balfour accepted arbitration again in the dispute over the frontier between Alaska and British Columbia. Astonishingly, the British arbiter decided in favour of the United States and against Canada – a decision that was very badly received by the Canadians.

Rudyard Kipling urged the Americans to “take up the white man’s burden” and assist Britain in the civilizing of “the lesser breeds without the law.” He was disillusioned with the response.

Joseph Chamberlain did not believe that the Empire would give way to the United States without conflict, and so determined on an Anglo-Saxon alliance to prevent it. If the British Empire and the United States did not combine to dominate the world, their divergent interests would surely bring them into conflict when America, following Admiral Mahan’s vision, could only expand at the expense of the British Empire.

It was realised in British ruling circles that the Empire was destined ultimately to give way toits great Anglo-Saxon cousin. That is the only explanation for the attitude of inferiority that British statesmen began adopting towards the United States at the height of their power.

It was ultimately decided to attempt to indirectly capture the United States, rather than attempt to defeat it in war. And the building of an Anglo-American Establishment, so that the British Empire could live on within its great Anglo-Saxon cousin – the future master of the world – became a significant project for the most advanced Imperialists in England, centred around the Round Table/RIIA/Chatham House group.

It was, therefore, determined to deal with America peacefully and to go to war with Germany. And if it were ever contemplated to cut America down to size after Germany had been dealt with, two exhausting wars with Germany – as a result of which the United States profited as a result of England’s difficulty – put paid to that notion.

This is how the United States moved away from Washington and became entangled in European conflict in the 20th Century.

After two years of Britain’s 1914 Great War on Germany, in October 1916, John Maynard Keynes issued an important memo from the British Treasury entitled ‘The Financial Dependence of the United Kingdom on the United States of America’.

The problem emerging was that the gold and securities accumulated by Britain over the previous 200 years were running out. Decades of capital accumulation gained by British Imperialist expansion in the 19th Century was being undone by the expense of both funding allies and fighting the Great War.

Britain was struggling badly to see off the enemies it had taken on and needed to deliver a knock-out blow to Germany and the Ottomans to win the war. To do this it continued to expand the war to stretch the enemy’s resources. It ran its Russian ally into the ground, preparing the way for the Bolsheviks in funding the Russian Steamroller until it wrecked itself.

In doing so Britain exhausted its accumulated overseas assets. As the war dragged on the British government forced its banks and citizens to sell off foreign investments to buy government debt. Its indebtedness to US banks to finance the continued expansion of the war placed Britain in a precarious position. The US had it over a barrel. If credit was cut off the war was lost.

By March 1917, Britain’s stock of Dollars was down to around one month’s worth of purchases on the US markets. It began to be realised that only an American entry into the war on the Allied side and the US government taking over Dollar financing of the war would prevent a great crisis and the need for Britain to settle with Germany. This would have represented a great defeat for the Empire, from which its prestige would never recover.

The US banks and economy were making a lot of money out of the war. However, the problem for Washington was that a large part of the US economy had become enmeshed on the side of the Entente at the behest of Anglophile bankers. The more Britain borrowed in America and the more it purchased from the US, the harder it was for President Wilson to disentangle the US from the fate of Britain and the Entente. In November 1916 a concerned Federal Reserve issued a note warning US citizen not to commit any more savings to Entente loans. British credit in the US collapsed.

President Wilson attempted to shackle the warmongering Anglophile US banks who fuelled the world war and impose a peace on Europe which would be the ruin of imperialism and the dawn of new progressive era in world affairs. He failed, however, and realised that because he could not initiate an ending to the war the US would have to join it on the side of the Entente to save itself from an economic collapse.

On 22 January 1917 Woodrow Wilson strode onto the rostrum of the US Senate. This was the first time a President had directly addressed it since the days of George Washington. The text of his speech was delivered to the major European capitals. Wilson’s speech made it clear that America was determined to shut down the World War. The US President demanded that all the parties to the Great War acknowledge the conflict’s futility. The war could have only one outcome: “Peace without Victory.”

Adam Tooze has written of Wilson’s January 1917 speech to the Senate:

“… the world he wanted to create was one in which the exceptional position of America at the head of world civilization would be inscribed on the gravestone of European power. The peace of equals that Wilson had in mind would be a peace of collective European exhaustion. The brave new world would begin with the collective humbling of all the European powers at the feet of the United States, raised triumphant as the neutral arbiter and the source of a new international order.” (The Deluge, pp.52-3)

If President Wilson had held to this position and withdrawn access to the finance from the Allies that enabled them to continue waging war, while negotiating a peace with Germany directly, the history of the 20th Century would have been completely different. The war would have stopped; there would have been no Bolshevik takeover in Russia; no humiliation of Germany; no Hitler etc.

Perhaps if Wilson had behaved in a Trumpian fashion the destruction of the 20th Century would have been aborted at conception.

But because Wilson did not follow through, it was British defeat and bankruptcy or US intervention by 1917.

This is how the US became entangled in the European war that Britain had made into a world war.

The war could only have been won through US participation, but when it was won the US Senate, bearing in mind the advice of Washington, decided to obstruct Wilson’s plans to regulate the global order with Britain. It believed the Treaty of Versailles and the other treaties and proposed mandates represented foreign entanglements best avoided.

Andre Siegfried noticed the peculiar relationship between Britain and the United States which developed after the Great War victory over Germany. Britain, which had always fought to establish and defend its supremacy in the world, was now seeking collaboration with another power in the post-War world it dominated. It was doing so through a tacit accord with the U.S. rather than a formal alliance. This, it was imagined might impose a Pax Anglo-Saxonia on the world like the Pax Romano of Emperor Augustus, through the power of two great navies.

Siegfried noted that the US was suspicious of being taken in tow by Britain and it was reluctant to engage in the project England was mooting, largely through Lord Milner’s men. The US had become a world power in the course of World War One through its activity in relation to Britain and Britain’s failure to defeat Germany through its original allies. But the US had reverted to its original foreign policy of George Washington, judging the moment to be premature to take hold of the world at that point. It was seemingly content to let Britain remain top dog, to blunder on and to weaken more, before it finally made its move.

At the end of the war, Britain’s total debt to the US stood at £7.4 billion ($125 billion today) which took until 2014 to fully pay back. During the war Britain sold much of its overseas investments to the US, which were previously a large source of income. As a result, the Empire could not be maintained as before, just as it had been expanded. Ultimately, Britain never really fully recovered from the economic cost of its war and its post-war economic weakness, alongside its massive foreign debt. This set the stage for the US to become the world’s principal economic power

President Woodrow Wilson gave way to President Harding:

“On March 4, 1921, the Harding Administration assumed office, and the British Government could no longer count upon the pro-British policy that President Wilson had consistently followed. It was imperatively necessary for Lloyd George to conciliate this new Administration in Washington. Large loans from the American treasury had enabled Britain to maintain financial solvency, and the Chancellor of the Exchequer ardently hoped that arrangements could be made with Washington that would ease the burden upon the British taxpayer. Heavy expenditures for new naval construction were out of the question, even though Winston Churchill in his most sonorous rhetoric announced that the British would not accept ‘any fettering restrictions which will prevent the British Navy maintaining its well-tried and well-deserved supremacy’.” (New York Times, November 27, December 6, 10, 1918)

The British attempted to avoid paying their war debts to America. They proposed a collective write-down of inter-Allied debt and pondered renouncing claims on the debts of their allies in a move aimed at shaming Washington into following Britain’s example to the British advantage. The Foreign Office approved this scheme to hold onto Britain’s “incontestable moral leadership of the world” against the US challenge. However, the US Senate rushed through a motion affirming that America would not cancel a cent of its claims on the war debts of the Europeans, including Britain.

President Harding decided on America First and imposed a naval agreement on Britain in 1921 that ended its command of the seas – something which Britain had maintained for over a century and had gone to war with Germany to uphold. At the Washington Conference, Secretary of State, Charles Hughes, opened the event by listing by name every ship of the Royal Navy the Americans expected the British to scrap to reduce them to the status of equality with the US Navy. Arthur Balfour, the British Foreign Secretary, meekly complied.

Along with naval parity the US also insisted that Britain not renew its alliance with Japan in the far east that had existed since 1902, fatally weakening the British Empire in Asia.

Siegfried observed the following in the 1930s as Britain took a “needs must” attitude to its new position vis a vis the United States. When one reads the passage one can see that Keir Starmer’s Britain operates in the same mode as Britain adopted in the 1930s in relation to Trump’s America:

“In order to preserve her supremacy on the seas, England has waged two great wars, one against the France of Napoleon, and the other against Germany under William II. In each case she was all but exhausted. To-day, in a mere decade, without a war, without a struggle, without seeming to care, this same England has renounced her supremacy, at least in principle, at the request of the United States.

We are forced to regard this renunciation as a loss of prestige. The English would have you believe that it is simply common sense, and that it had to be done. If they feel humiliated, they certainly do not show it. Furthermore, Balfour and MacDonald, the two men who in 1921 and 1929 negotiated the agreements which led to the present solution, both returned home from Washington in triumph. How do the British really feel about it in their innermost hearts?

Since the beginning of the century the British Government seems to have made up its mind never to oppose the United States. It invariably gives way, as if it had decided always to do so. One recalls the line of Corneille: ‘Ah, ne me brouillez pas aver la Republique!’ (Don’t mess with the Republic!)

England finds that she is faced with a growing force against which frontal resistance counts but little. She also knows that in the case of conflict between the two nations, it would be difficult for Canada to take the side of the Mother Country…Little by little this reasoning is being applied not only to Canada, but to all British possessions lying within the American zone… In the whole zone covered by the Monroe Doctrine, the fiction of sovereignty persists, although it is no longer complete – simply, it must not be mentioned. The vase is cracked. Do not touch it.

England feels that she is confronted by a sort of elemental force, and has therefore put to one side all thoughts of competition in armaments… In what spirit have the British people received this new attitude, so little in keeping with their traditional pride? It has not affected the masses, and in the upper classes an important section, probably the most important, has accepted the fait accompli without grumbling. We would be perhaps right in saying that in this matter England tolerates from the United States what she would never tolerate from any other power. ‘Needs must…’ the English seem to say…

Perhaps they simply consider that the Empire must eventually dissolve into a greater Anglo-Saxon ensemble… If the Empire is destined to disappear, it could be replaced, to a certain extent, by a union of English-speaking peoples, which would bring the Anglo-Saxon race still more powerfully together…

This reaction is difficult for the French to understand and… will always be incomprehensible to the French. This reaction to the United States partially explains Britain’s lassitude in not striving to retain by force her political control of the world. She is beginning to feel old. She naturally makes way for youth, especially since the youth is a member of her own family… By paying this price, the Empire can exist indefinitely in its present form, and British commerce can prosper.” (England’s Crisis, pp.238-43)

Although Siegfried observed England gravitating toward the Atlantic, he did not believe that England could ever really escape Europe:

“England cannot cut herself entirely adrift from the Continent which lies so close to her, any more than Europe can consider herself complete without those two little islands which lie at her gates. Neither politically, economically, nor intellectually, can one long admit the thesis of a non-European England, out of touch with the Old World… Europe… is an irreplaceable market, and England realises that her prosperity rises and falls in sympathy with that of the Old World. It is sheer folly to think she can disentangle herself from Europe.” (pp.245-6)

Siegfried observed that rather than choose between the Anglo-Saxon world and Europe

“England will not choose at all. Faithful to her tradition and her genius, she will hover between the two groups, without giving herself completely either to one or the other. A European England is a dream… Vitality and flexibility have always been the strongest traits of the British nation… The Empire, and the spirit on which it thrives, have unlimited powers of adaption and life.” (p.251)

In the late 1930s, after appeasing Hitler at Munich, Britain gave a security guarantee to Poland. The appeasement is well remembered but the security guarantee that resulted in a second world war is not so often recalled. Poland, which Britain had given its security guarantee to, in order to prevent war, was decimated in the war that the guarantee failed to prevent, and it became part of the Soviet world for two generations. Britain did not fire a shot in the defence of Poland.

While there was much talk of Munich appeasement recently in Europe with President Trump’s overtures to Russia, the Churchillian version of history which Europeans and dumber Americans have swallowed, does not recall the disastrous security guarantee Britain gave to Poland that started a world war.

President Trump, or someone close to his ear, seem to have a more realistic view of history than those under the spell of Churchill’s fantasy history.

R.W. Thompson’s 1960 book The Price of Victory is an interesting read. It is about how D-Day 6th June 1944 marked the end of British power and the ascension of the US. It was preceded by a significant deal in mid-1940 in which the US broke its neutrality in the war by illegally supplying Britain with a couple of hundred redundant, reconditioned destroyers in return for the surrender of British sovereignty to the U.S. in a number of territories, the first action of its kind since 1776.

The British author, Thompson, noted that

“This day, the 6th June, was Britain’s Swan Song… On D-Day Britain had paid, stripped to her uttermost farthing… On D-Day Britain ceased to be a major power in the world, no longer even able to shape her own ends. The new Europe would not be hers, or of her making. George Washington might have trembled in his grave!” (pp.257-8)

This is the true story of Britain’s Second World War, stripped of its Churchillian salvage narrative. It describes a war being fought by allies for entirely differing reasons and a victory over Germany that was a triumph for the USSR and US and an utter defeat for British power all over the world.

Thompson argued that having put the whole of her overseas financial assets into the bungled World War Britain she declared on Germany Britain had, by 1944, “shot her bolt.” The New World arrived late to save the old, but its objective was not the maintenance of the Old Order.

Thompson pointed out that for Britain the Price of Victory was the loss of some of her overseas territory, her remaining accumulated wealth of Empire and her reduction to second-class power status. For more than a year after the entry of the US into the war Britain had to bear the brunt of the expansive War she had declared, in the Middle East, Malaya, the Atlantic and at home. It was thereafter inevitable that the initiative and the key decisions on grand strategy would pass into the hands of the United States and Russia.

Britain’s bungled war of 1939 was the occasion for Washington to finally relegate Britain to the status of a second-class power – a status from which it could no longer threaten the security of the world. This is implicit in Roosevelt’s dealings with Stalin and the side lining of Churchill. Trump/Putin comparisons with Roosevelt/Stalin are unspeakable.

A writer in the British Naval Review of 1960/1 assessing Thomson’s book ruefully noted:

“Though the author does not say so, this divergence between the U.S.A. and British world aims has been made abundantly clear since the end of the war, and the book gives some understanding of how the United States have done more to bring about the downfall of the British Empire as such than ever the Germans did in two wars.”

But Britain’s badly bungled Second World War that devastated Europe and brought Soviet forces halfway across Europe to Berlin had great implications for America and the policy of George Washington.

America could no longer maintain itself from foreign entanglements. It had, this time, to maintain its European engagement to save Europe from communism, rebuild it and finance it to put it on a firm economic foundation again. It gathered the warring Europeans into the European Economic Community and established NATO in 1949 for collective defence.

The US suffered one of its greatest reverses in Vietnam, when it was drawn in to bolster the French imperialist hold on the country against the substantial resistance it had generated, and which was overwhelming it. This was another foreign entanglement given to the US by Europe.

The US is sometimes referred to as an empire. But it was very different from the British Empire it replaced. The US became a hegemon in the era of nationalisms, that Britain helped globalise in the service of its Great War of 1914, but which it could not subvert after the victory because the US, with its anti-colonial spirit, had come upon the scene.

The Cold War that the US managed for the West ended suddenly and unexpectedly. In 1990 the Soviet Union suffered an internal collapse under its last General Secretary. And the US, flushed with success, and believing it had did for the USSR, rather than Gorbachev, proclaimed a New World Order and began marching eastward toward Russia with NATO until it snared the Ukraine in a Washington organised coup. It seems that the problem with Russia was not its communism but the fact it was Russia and when its East European buffer zone was dismantled this became part of the new Drang nach Osten.

In the ecstasy of victory, the advice of George Washington was ignored in favour of the universalising of the West and “the end of history.” Georgia and Ukraine were earmarked for NATO until Putin put his foot down.

It was proclaimed widely by the US foreign policy establishment that the resurgent Russia, under Putin, had been lured into over-reach when the Special Military Operation was launched in February 2022.

And to make sure the Special Military Operation was turned into a full war, Boris Johnson did his bit to obstruct a settlement at Istanbul, only a few weeks after the conflict began, when Kyiv was surrounded and Zelensky was ready to concede.

But it now appears that it was the US and Europe who were guilty of over-reach rather than Russia, and the wisdom of George Washington’s advice has been demonstrated and appreciated by President Trump, much to the chagrin of those who wish to continue to entangle the US in European wars.

It is not surprising that the pain and anguish is felt most in the British political elite, who in previous wars were said to be willing to “fight to the last American” and were happy to goad Kyiv to “fight to the last Ukrainian” facilitated by US dollars.

But it seems that President Trump and his men cannot be convinced that this represents anything resembling a good deal for the USA. They wish to return to the Founding Fathers.

And J.D. Vance has alarmed Europe by stating: “America is not just an idea. America is a nation.”