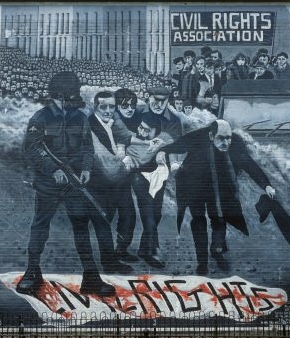

To mark the 50th anniversary of the administrative massacre in Derry I have posted the section which deals with Bloody Sunday in ‘Resurgence, 1969-2016: Volume Two of The Catholic Predicament in ‘Northern Ireland’ by Pat Walsh (Athol Books, 2016) pp. 185-8.

Testing the Nationalist Will

It was the British escalation of the conflict, after failing to get the SDLP to come in from the cold, in order to defend its settlement of 1920/1, its pseudo-state in the Six Counties and its sub-government at Stormont that produced Bloody Sunday in Derry.

The sequence of events from the summer of 1971 ran like this: Gerry Fitt and John Hume led the SDLP out of Stormont into the Alternative Assembly in Dungiven; The IRA campaign received a great moral boost at having detached the reformists from accomodationist politics and went into a higher gear; Internment was introduced in an attempt to stem the rising tide of violence but led to a further intensification again; Bloody Sunday was an attempt to frighten Catholics off the streets but led to a further escalation of the War that finally put paid to Stormont.

The Anti-Partitionist offensive, both military and political, was reaching its high point in early 1972. There was a general feeling in Nationalist Ireland that an ending of Partition was possible through the immense effort that was going on in the North. The ‘Constitutional Nationalist’ Irish News was selling its “Long Kesh Calendar” to its readers for 25p (26.1.72). Next to its Anti-Internment editorials and its “Pro Fide et Patria” masthead it had articles such as “Mass in Long Kesh” in which Fr. Noel Fitzpatrick summoned up the spirit of the Martyrs in support of the Insurrection:

“One seldom hears the Mass prayers answered with so much vigour and meaning as one does in the camp… Mass usually ends with the singing of ‘Faith of Our Fathers,’ sung with great gusto, especially that part about ‘in spite of dungeon, fire and sword.” (7.2.72)

All shades of Nationalist opinion, with religious backing, were gathering behind the great effort of the community against Stormont.

The objective of the Derry march was described by its organiser, Kevin McCorry of NICRA, a few days before the Sunday, as the culmination of the disobedience campaign to destroy Stormont:

“We are on the streets to demonstrate rejection of the Unionist regime by a large section of the community here… 30,000 people withholding rents, 10,000 people throughout the North refusing to pay rates, and other payments. Opposition representatives have been out of Stormont for six months, non-Unionist Councils have collapsed. Over this last month, thousands have demonstrated defiance of Stormont’s laws in the streets.”

The march, which the Stormont Government declared illegal, was intended to be a decisive confrontation with the “Orange State” by the organisers:

“It was no easy decision… for a struggling people to leave the relative safety of their homes to brave batons, rubber bullets and C.S. gas, but this was the people’s way of pressing the issue to a decision.” (IN 26.1.72)

NICRA demanded the unconditional release of all internees; abolition of the Special Powers Act; the withdrawal of the British Army from Republican areas; further Civil Rights legislation from Westminster and an end to the Unionist administration at Stormont.

On 30th January, at the Derry march, the British Army shot dead 13 unarmed men. One other victim died later. In the aftermath of the massacre Hume famously said on a BBC programme that the feeling was that it was now “a United Ireland or nothing” (IN 1.2 72), and the SDLP called on all Catholics in public life to withdraw their services.

The mass killing had all the characteristics of an Imperial ‘administrative massacre’ on Britain’s part in which the shooting of demonstrators/rioters was meant to deter others from bad behaviour, like at Amritsar, India. ‘Al Carthill,’ a senior Justice in the Bombay High Court said in a 1924 book that the ‘administrative massacre’ was a useful device when applied to natives but was seldom used in Britain:

“There are, however, precedents in British history which tend to show that, when the occasion arises, the British will display a surprising energy and thoroughness in this branch of administration. The ‘administrative massacre,’ as this kind may be called, is, of course, familiar enough to the Oriental.” (The Lost Dominion, pp.93-4)

A few days before the massacre at Derry it was revealed in The Guardian by Simon Hoggart that British Army units in Belfast had requested and obtained the withdrawal of the Paratrooper Regiment from their areas of operation because “the Army now believes that the absolute minimum of force must be used in these areas to prevent the local community from becoming more disaffected with the Army.” The Paratroopers, described by one British Captain as “little better than thugs in uniform,” obviously felt that the British Army was being too softly-softly in its approach and the Catholic insurgents needed to be taught a tougher lesson. (IN 26.1.72)

It later emerged that Major-General Ford, who was impatient with the developing street disorder in Derry, and who deployed the Paratroopers, had written a paper to the GOC Tuzo saying that it was time to stop the hard-core rioters that had arisen in Derry since Internment and said he was “coming to the conclusion that the minimum force necessary to achieve a restoration of law and order is to shoot selected ring leaders amongst the DYH (Derry Young Hooligans, P.W.), after clear warnings had been issued.” (Peter Taylor, ‘Brits: The War Against the IRA, p.88)

The same regiment that carried out the massacre, the Paratrooper shock troops of the British Army, had earlier carried out another massacre in August 1971 in Ballymurphy with much the same purpose – teaching the more troublesome Catholics a lesson. But its effect, like the Derry event, was precisely the opposite and led to many demonstrators and rioters becoming IRA volunteers instead. It, unlike Amritsar, did not work.

The probability is that Bloody Sunday was an event, like the earlier massacre in Ballymurphy – that was unseen by the TV cameras – to test the will of the Nationalist community. Despite 2 Inquiries it will probably never be known if there was political connivance, perhaps through “nods and winks,” in the decision to embark on it or it was a decision taken at some level of the British Army, on the day or beforehand.

Ian McAllister, in his book on ‘The Northern Ireland Social, Democratic and Labour Party’ saw Bloody Sunday as the inevitable outcome of the adoption of a military solution after the failure of the British Government to lure the SDLP back into Stormont. However, in its effects it ultimately spelled the end of Stormont and put a new political initiative on the table:

“The action in shooting the marchers was in fact the logical extension of a military policy designed to extirpate the IRA, but when faced with this, and an adverse press abroad, Westminster backed away.” (p.110)

When the massacre did not sap the Nationalist will, but strengthened it, Stormont had to be sacrificed to alleviate the situation for Britain. As William Beattie Smith commented: “The Derry killings effectively terminated the strategy of using military force to uphold the Unionist administration.” (‘The British State and the Northern Ireland Crisis 1969-73’, p.182)

Robert Ramsey (Principal Private Secretary to the Unionist Prime Minister) rang Brian Faulkner on the night of the shootings. Faulkner, who did not believe the British Army version of events that they had killed ‘terrorists’, said: “This is London’s disaster, but they will use it against us.” (Ring Side Seats, p. 98). As Faulkner said the total responsibility for Bloody Sunday lay directly with Whitehall. Stormont did not control the Army that carried it out. But it was Stormont that paid the price for it.

The events of Bloody Sunday in Derry threatened to produce a great escalation of the conflict. Catholic politicians intensified their withdrawal campaign and the IRA’s military offensive surged. The last remaining Catholic legal functionaries and bureaucrats, like Maurice Hayes, who had remained at their posts during the anti-Internment campaign withdrew from the system.

But, in fact, what was occurring was a general backing away from taking the conflict to a higher level.

A march was organised in Newry for the Sunday following Bloody Sunday. Nationalist politicians initially urged all Catholic Ireland to be there and a mass convergence on the town from all parts of the country was predicted. Train and bus timetables were altered to take the Nation to Newry and dire predictions were made of a possible further massacre.

The situation had all the makings of a High Noon in the National War. It prompted the British Prime Minister, Edward Heath to make an unprecedented appeal to Cardinal Conway, Cardinal Heenan and the Taoiseach to use their influence to have the march cancelled. It was reported that Lynch had set up “field hospitals”, South of Newry, for the impending conflict (IN 4.2.72).

But the Dublin Government and the Southern Establishment, which had worked things up after Bloody Sunday, thought again and spent the second half of the week calming things down and urging restraint. And the burning of the British Embassy in Dublin acted as a safety valve in the situation.

In the event Catholic Ireland and Protestant Ulster did not come to a final reckoning. There was a strong all-class Nationalist turnout from the North but numbers did not materialise from the rest of the country as predicted earlier in the week. The march passed off peacefully.

In the moment of truth a decisive conflict did not materialise. Perhaps if all Ireland had converged on Newry the framework of the conflict would have been altered qualitatively with the result that anything was possible – even a Republican victory. But it didn’t and the moment passed like at Clontarf in 1843 when Daniel O’Connell declined the challenge.

It was probably a turning point. From that moment Southern public opinion began to disengage from ‘Northern Ireland’ and the Northern Catholics were on their own in the situation that had developed, to make the best of things for themselves.

Thank you Pat. Very sad day.

Betula

>

LikeLike