“My interest in Persia was aroused some years ago by the writings and the speeches of Professor Browne, and my interest to it was attracted because I have all my life thought that one of the greatest outrages against humanity that can be perpetrated is to kill the soul or the civilization of any nation… I am afraid that in these modern days the vast majority, at all events in Western Europe, have set up a false standard for the guidance of their own judgment as to what is really valuable in the civilization of today. We in Western Europe are so handed over to materialism that we seem to think the amount of manufactures produced and the wealth realized is really the only standard by which you can judge a people, or that a nation like Persia, or many other nations who are no longer war-like, wealthy, or able to defend themselves very well, do not matter; and that it is no loss to mankind if they are wiped out of existence and forgotten…

When I learnt from Professor Browne that there was a nation with so great a historic past, so great and so well founded a national pride, and a nation who had contributed so enormously to the spiritual wealth of mankind by its arts and by its literature, in the condition that Persia is today, my deepest sympathies were aroused….

Another thing is perfectly plain: That we in the West have inflicted great injustice and injury on many of the Eastern races… I confess that my sympathies go out to all these races… who have a historic past, self-consciousness, which in my opinion is the necessary seed-bed of great achievement…” (John Dillon, speaking to the Persia Society in 1912 in praise of Professor Edward Granville Browne)

John Dillon was undoubtedly Persia’s greatest parliamentary supporter in Britain prior to the Great War. He had exposed the British concentration camps in South Africa a few years earlier and also showed a keen interest in Indian and Egyptian independence. Dillon was a very substantial Irish nationalist/British liberal, anti-imperialist. That is a combination which modern Ireland would find hard to contemplate today because it has made no real attempt to get to grips with the relationship Redmondite Home Rule had with Imperialism. That relationship negated the influence of John Dillon and has created an eccentricity of him in Irish history writing. And if I recollect correctly, the only biography of him, by F.S.L Lyons hasn’t helped. It has one solitary reference to Persia in over 500 pages and seems to regard Dillon’s interest in foreign policy as a kind of distraction. That really is a poor reading of Dillon and shows little understanding of the fundamental importance he attached to this aspect and its bearing on Ireland.

Dillon was certainly the man Professor Browne thought most highly of, among all the friends of Persia in Britain. Dillon could never join the Persia Society, owing to restrictions imposed on members of the Irish Parliamentary Party from being members of other organisations. He was, however, the most effective critic of the Persia policy of Sir Edward Grey as British Foreign Secretary from 1906.

The most important figure who championed the cause of reform and democracy in Persia was the extraordinary Professor of Arabic, Edward Grenville Browne, the Cambridge Orientalist. It was he whom Dillon attributed his knowledge about the country to. Browne had journeyed to Persia in 1887 and afterwards penned his famous book, A Year among the Persians (1893) with its vivid accounts of metaphysical and theological discussions with a wide range of Persians and their faiths, and the extraordinary four volume Literary History of the Persians (1902). Professor Browne’s first love had been Turkish, which he learnt with a view to joining the Ottoman Army after developing an affinity with the Turks after the Russian-Turkish war of 1877-8. Although he believed the Persians to be a more original and talented people than the Ottoman Turks he noted in his introduction to The Press and Poetry of Modern Persia that the Turks had introduced the ideas of fatherland, nation, people and liberty to the region and given them their modern significance. Browne had been entrusted with the completion of E.J.W. Gibb’s magnificent five-volume History of Ottoman Poetry and remained an admirer of the Ottoman and Azerbaijani Turks until his death in 1926.

Although Browne returned from Iran to Cambridge in 1888 his reputation soared among Persians after his defence of the Constitutionalist Revolt in 1906 and his pamphlets and newspaper articles in support of the idea of Persian democracy. A later book The Persian Revolution of 1905-1909 (1910) details the course of the Constitutionalist movement and its defeat, giving a unique voice to Persian opinion within its pages.

Edward Browne’s view of the Persian revolution can be summarised as follows: It involved a group of patriotic men, representing progress, freedom, tolerance and national independence standing up against injustice and tyranny, represented by the Shah, his Court and reactionary supporters. The Constitutionalists succeeded in forcing concessions from the Shah that represented the beginnings of Persian democracy, but they were eventually deprived of the full fruits of their labours by the Persian reactionaries, aided and abetted by Russia and Britain, through the policy of Sir Edward Grey. The Persian revolution was thus, a lost liberal revolution. And that is how John Dillon saw it too.

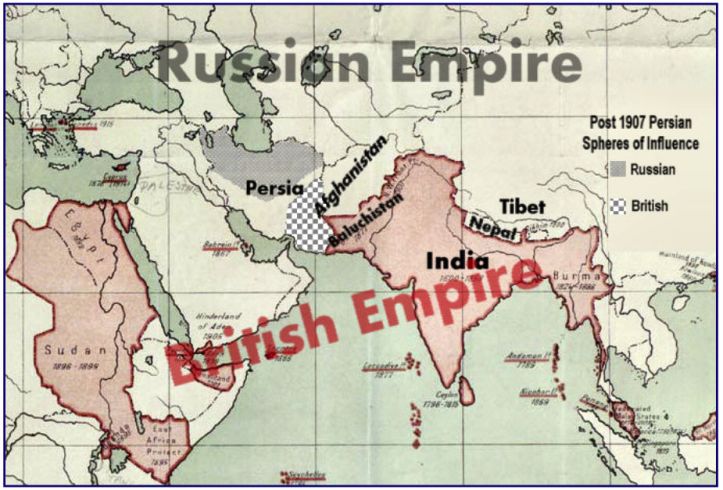

The event which turned the situation against the Persian Constitutional Revolution was Sir Edward Grey’s Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907, which settled a number of territorial issues between the two Powers, including Persia. In the Agreement Persia was partitioned into 3 zones of influence, with the Tsar taking the Northern part, the British absorbing the South East and an intermediate “neutral” zone in between.

This Agreement suspended “The Great Game” of Imperial rivalry between England and Russia in the interests of the British Balance of Power Policy in Europe.

The ground for the 1907 Agreement with Russia was prepared by Sir Edward Grey and the City of London through a 90-million-pound loan made to Russia in 1906. The disastrous war with Japan had caused a financial crisis in Russia with the Tsarist State buckling under the strain of maintaining the Gold Standard as its Bonds rapidly depreciated in value. Russia had a long-standing financial relationship with French banks, but after the 1904 Entente France and Britain began to work more closely together and the British Foreign Secretary insisted in British participation in the 1906 Bond issue. It may have seemed strange that Britain was ready and willing to bail out its chief enemy in the world at a time of its great financial crisis, but Grey obviously saw a great opportunity to tie Russia into a relationship, when it was most vulnerable. It was this relationship of Russian financial dependence on Britain which drove the Tsarist State to destruction in 1917, having taken on Britain’s war on Germany and the Ottomans.

Many in England, including Lord Curzon, felt that Sir Edward Grey had been too generous in making this unprecedented concession to the Russians, which involved ceding to them the most populous parts of Iran. The 1907 Convention undoubtedly undermined Britain’s position among the Persians. Despite the best efforts of the British Ambassador at Tehran, Sir Cecil Spring-Rice, popular opinion believed Britain had betrayed the Persian democratic cause by allying with the Tsar to carve up the country.Ambassador Rice, who was a reluctant instituter of the new policy, confided that “their natural ally, England, went over to the enemy and put her hand in that of the oppressors.” Persian protest at the Convention was exclusively aimed at Britain, rather than Russia, which had no democratic pretensions. That the Persian public had no idea of the existence of the 1907 Convention until its announcement caused particular insult. It was said that “England had definitely withdrawn her opposition to Russian aggression in return for a share of the spoil”.

In 1911, beset by the Anglo-Russian despoilers, the Iranian National Assembly appealed to the US for a financial adviser to sort out their finances. Morgan Shuster was loaned to them and appointed Treasurer-General for 3 years. In the teeth of opposition from the British and Russians, Shuster set on foot a plan of reform to release Persia from the financial servitude the country had been shackled through the 1907 Convention. To raise necessary finance, he needed to recruit a force to collect it from the rich landowners. He found the perfect leader for this force in Major Claude Stokes, an Indian Army soldier who had supplied Professor Browne and John Dillon with the inside information from the Tehran legation to expose Grey’s manoeuvres in England. But when Stokes accepted the appointment Grey blocked it and sent Stokes back to India. The Grey and the Tsarists focused their attention on getting rid of Shuster.

Dillon harassed the British Foreign Secretary in the Commons over the deporting of Major Stokes but to no avail as the shifty Grey evaded his questions.

Morgan Shuster later related the story in his book, The Strangling of Persia, of how the National Assembly, assailed by foreign influence and a corrupt Palace elite in league with the despoilers, were forced to dismiss their finance adviser, and prior to its final dissolution, to give an undertaking never to import a foreigner again, without the permission of the 2 supervising Powers.

Grey’s policy was really inexplicable from a British strategic, commercial and democratic point of view. It looked, to all intents and purposes, a very bad deal – verging on a surrender – for the British Empire to sign, only a few years after Tsarist State had been humbled by Orientals. There must have been more to such an unusual concession?

The wagers of the Great Game in England and in Britain’s Indian Empire who criticised the 1907 Convention and Grey’s Persian policy did not know that the Anglo-Persian Agreement was part of a much wider diplomatic process to prepare the ground for a confrontation with Germany, in which extensive preparations had been made since 1904. Only in that context, did the concessions made to the Tsar make sense.

The real purpose of the 1907 Agreement did not become apparent until after the Great War. As E.G. Jellicoe commented:

“Persia at this time by her geographical situation was at the confluence of British influences from India and Russian interests in the North. In 1906… some violent influences had provoked a revolution in Tehran, and this immediately strengthened the hands of Russian and British diplomats and afforded them a pretext for agreeing the terms of still another ‘understanding,’ which following in the spirit of the Anglo-French precedent. This was intended either verbally or by implication, to secure, in Lord Haldane’s words, ‘the assistance of Russian pressure’ on the ‘eastern’ frontier of Germany, and which, while affirming the integrity and independence of Persia, expressly divided that country into three zones…. Except as part of the policy of a great military enterprise, there never could have been any necessity to negotiate with Russia to secure British interests in the Persian Gulf or for bribing Russia in order to secure the peace of Asia… Germany alone stood in the way of our foreign policy in diplomacy. The Baghdad railway was the stumbling block to the development of Persia on the lines of… Lord Curzon’s book.” (Playing the Game, pp.65-6.)

By 1912, after the departure of Shuster, the Persian Government existed in little more than name. Russian troops occupied the northern provinces, and the independence of the country was merely a pretence. The state was bankrupt, its troops and administrators left unpaid, and it was unable to quell widespread internal disorder which came from discontent.

The English Radicals and friends of Persia faded in their efforts and the “Grey Must Go!” campaign of 1911-12 against the Foreign Secretary’s policy, that they believed was heading to disaster petered out, before disaster came in the shape of the Great War of 1914.

There is a strong correlation between this and the intensification of the Irish Home Rule crisis in Britain from late 1912 to 1914. As the parties in Britain polarised over the issue of Union versus Irish Home Rule and drifted toward civil war, the Liberal Radicals found themselves cohering around Grey and the Liberal Imperialists they had opposed in Persia. Criticism of Grey’s foreign policy became muted until it became too late, in August 1914, when the full realisation of what had been going on in the background was finally discovered. And then the Liberals were faced with a fait accompli that Persia had alerted them to, but which they failed to derail.

As for John Dillon – he was wrong-footed by Redmond’s offer to England. At the vital hour he conceded his Liberal principles to his Chairman, hoping that a quick victory and a militarisation of a loyal Nationalist Ireland, would place it in an advantageous position vis a vis Home Rule against the Unionists, who had brought the gun into Irish politics and scotched Home Rule at Larne and the Curragh.

But a long war ensued which advantaged the Unionists, and the Irish Party was destroyed in the course of it.

And Persia, which declared neutrality in the Great War was told it had no right to be neutral in a war for civilization. It became a launching pad for Tsarist and British military operations against the Ottomans and a battlefield until 1921, in which millions died from famine, as Britain absorbed the whole of the country, after the Tsarist collapse in 1917.

In 1919 a Treaty was presented by Lord Curzon to the Iranians, making their country a puppet state of Britain. However, the Iranians resisted and availing of the Bolshevik resurgence in late 1919 they stonewalled, frustrating Britain’s plans.

Britain, of course, was not finished with Iran – as it was not finished with Ireland.

Whilst Britain was forced to back away from attempting to make Persia a Protectorate after the Iranians were imbued with confidence by Wilsonian idealism and the advance of Soviet power into the South Caucasus in 1920-21, it could never give up its hold on Persia because of its oil.

The interests of a country could never coincide with the interests of a private company, particularly one owned by a foreign nation. The acquisition of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company by the British Government in 1912, with the company governed via a British director with veto power on the board, meant that the Persians thereafter came up against the full force of British national interests, rather than those of a private concession. Oil became a critical commodity, not only on the seas but on land and in the air.

Reza Shah, Iran’s new strongman leader, put in power by General Ironside’s coup, was affronted by the British presence in Abadan. The Anglo-Persian Oil Company acted as if it were not part of Iranian society at all, refusing to come under Iranian law by insisting that its presence was a product of a treaty it had negotiated with the local sheikh and not with Tehran.

The Persians had got a pitiful deal from the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, with huge profits being siphoned off by Britain and derisory sums paid annually to the Persian Government for its resources. War reparations were demanded by the company for the Persians’ failure to protect the oil installations during the Great War, which had resulted in slight damage. From 1914-21, 8 million pounds in concession fees were held back from the Persian Government. In 1917 the Oil Company used the precarious financial position of the country to negotiate an extended concession from 1961 to 1986 and an alteration in the calculation of the royalty that was hugely beneficial to the Company and detrimental to the Persians. The British Admiralty obtained their oil from Persia at only 10 per cent of the going rate. A British financial advisor revealed that creative accounting resulted in gross underpayments to the Persian Government on its 16 per cent stake in the profits. It was the British oil company which defined what its profits were. Whilst output quadrupled revenues to Persia declined.

Reza Shah decided to put a stop to this, angered by the Oil Company’s decision not to pay its royalty when the oil prices slumped in 1931. He informed the Company that the original concession, signed under duress, had ended and offered a new one on improved terms for Iran. Britain conceded but bided its time.

In 1939 Iran declared neutrality in the Second World War. However, the British and Russians invaded, securing the oil fields and refinery in Abadan. Iranian resistance was futile, and Reza Shah was put aboard a British ship at Bandar Abbas and transported to South Africa, where he died. For the rest of the War Iran was under Anglo-Russian control, as it was during 1914-17.

After the War Stalin attempted to unite the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic with Azerbaijan Province, south of the Araxes River. When the US put up resistance, Stalin was forced to back down, the Americans alone having the atom bomb at this time, and war being risky in such circumstances.

Reza Shah’s young son, who was weak and suitably malleable, was put in charged by the British, with the Royal Navy guarding his only trade routes in the Gulf and the Anglo-Persian Oil Company dominating the Iranian economy. In 1948 a cut in the Oil Company’s payments to Iran, bolstered by the British Government’s order for all British companies to limit their dividend payments, sparked trouble in Iran, as in 1931.

Dr. Mohammad Mosaddeq rose to power with the simple idea that the Anglo-Persian Oil Company was at the root of all problems for Iran. He called for the nationalisation of the oil industry to recover the national assets of the country. Challenging the British Government, the victorious superpower after the Great War, with its Empire flanking Persia to the West and East, risked war and occupation of its oil fields. So, it was only in 1951 that Iran, nationalised its oil.

With Mosaddeq’s popularity soaring the young Shah was forced to appoint him as Prime Minister in May 1951. Prime Minister Mosaddeq decreed the oil industry nationalised. The British Cabinet was divided as to how to respond. Some urged an immediate show of force to seize Abadan, but the US, fearing this might lead to Stalin seizing Azerbaijan province in response, warned Britain off this course. The British Government in conjunction with the Oil Company decided on the strangulation of Iran’s oil exports to bring Mosaddeq and the young Shah to heel. The US Secretary of State urged the British to settle with the Iranians before Soviet influence grew in the country.

The British disagreed with the Americans that Communism was about to replace Mosaddeq, the Constitutionalist. They believed a more compliant Iranian Government that would do London’s bidding was possible. It was decided, therefore, to play for time by entering into negotiations and to use more covert methods to neutralise Mosaddeq. Anthony Eden was confident that British Embassy staff and intelligence Officers could do their work as always, in regime change. Sir Donald Logan, at the British Embassy in Tehran and Foreign Office recalled: “Our policy was to get rid of Mosaddeq as soon as possible… The two years he was there was too long for our thinking.” (See C.M. Woodhouse, Something Ventured and Kermit Roosevelt, Countercoup: the Struggle for the Control of Iran, for the inside story of the coup from British and American participants.)

The British promoted an opposition in Iran to Mosaddeq. The Embassy and Intelligence Officers helped organise and coordinate it to engineer a break between Mosaddeq and the Shah. The British bribed prominent Iranians with suitcases of money and even imported arms for use by tribesmen against the Tehran Government. The Shah became frightened by the British moves and fled the country. The British then, working on the Red scare atmosphere prevalent in the US, with warnings that a Tudeh/communist takeover was imminent, convinced Washington to go along with a coup against Mosaddeq, supplying a list of possible replacements for American approval.

The Churchill Government authorised the coup for August 1953. Mosaddeq was overthrown and put on trial for treason. Although he was found guilty by the kangaroo court his defence in open military court had a dramatic effect on the Iranian people. He was sentenced to 3 years in solitary confinement.

Dr. Mohammad Mosaddeq was popular, patriotic, incorruptible and dedicated to liberal democracy. He dominated the nationalist movement and had the mass support of the people to make Iran a sovereign, independent country. However, the British were determined to get rid of him because he threatened their economic interests in Iran. The Anglo-Iranian oil company was the largest single British overseas investment, and its income was vital to a British Government after the Second World War, when rationing and austerity were features of the victory that resembled more a defeat. In such circumstances, economic exploitation of Iran’s oil resources predominated over support for assisting the development of a liberal democratic Iran. By plotting against and finally overthrowing Mosaddeq with the restoration of the autocratic Shah, the British Government effectively ended Iranian democracy and put Iran on the course that ended with the Islamic Republic in 1979.

On 15 April 2024 that product of the British Indian Empire, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, made a statement to the House of Commons on “Iran’s attack on Israel” in which he said:

“On Saturday evening, Iran sought to plunge the middle east into a new crisis. It launched a barrage of missiles and attack drones towards Israel. The scale of the attack, and the fact that it was targeted directly at Israel, are without precedent. It was a reckless and dangerous escalation. If it had succeeded, the fallout for regional security and the toll on Israeli citizens would have been catastrophic, but it did not succeed… With this attack, Iran has once again shown its true colours. It is intent on sowing chaos in its own backyard—on further destabilising the middle east… We must uphold regional security against hostile actors, including in the Red sea, and we must ensure Israel’s security. That is non-negotiable and a fundamental condition for peace in the region. In the face of the threats that we saw this weekend, Israel has our full support… The conflict in Gaza must end. Hamas, who are backed by Iran, started this war. They wanted not just to kill and murder, but to destabilise the whole region… Saturday’s attack was the act of a despotic regime, and it is emblematic of the dangers that we face today. The links between such regimes are growing. Tel Aviv was not the only target of Iranian drones on Saturday; Putin was also launching them at Kyiv and Kharkiv. And who was the sole voice speaking up for Iran yesterday, seeking to justify its actions? Russia… The threats to stability are growing, not just in the middle east but everywhere, and we are meeting those threats, time after time, with British forces at the forefront. It is why our pilots were in action this weekend. It is why they have been policing the skies above Iraq and Syria for a decade. It is why our sailors are defending freedom of navigation in the Red Sea against the reckless attacks of the Iran-backed Houthi militia. It is why our soldiers are on the ground in Kosovo, Estonia, Poland and elsewhere, and it is why we have led the way in backing Ukraine, and we will continue to back it for as long as it takes. When adversaries such as Russia or Iran threaten peace and prosperity, we will always stand in their way, ready to defend our values and our interests.”

Unfortunately, there are no more John Dillons in Ireland to tell the World what Britain did to Persia and how it subverted Iranian democracy. Or how it created what is now Israel and virtually everything else that makes for the Middle East today out of its Great War of 1914.

published in Irish Foreign Affairs, Summer 2024